I started buying cassettes when I was a teenager because they were cheaper than vinyl, more portable, and because I like to collect musical objects. They were passé then, and remain such, but my tapes are a cherished personal archive. I listen to them now and again because they give me a different way into music.

These days I mostly listen to music on Spotify, as I’m sure most of you reading this do. It’s a great interface for music in a lot of ways— there is a reason it’s been so successful. Recently, though, there has been a lot of writing about the perils of the platform— I just read Liz Pelly’s “Mood Music”, which I highly recommend, and which outlines some pretty shocking revelations about the ways the company inflates numbers, preferences music licensed from ghost artists, and has stratified the already backwards winner-take-all model of the music business. Beyond those more macro concerns, the book has also been making me think more critically about the way Spotify has influenced my personal relationship with music.

With Spotify, sometimes it’s hard to summon the focus to feel the music on a deeper level. I get distracted by the possibilities of skipping, changing songs, rearranging, playing god. Its integration with the rest of my life is convenient, but sometimes I don’t want music to be integrated. Sometimes music is an ocean that I want to swim in. Part of the fun of getting in the water is disconnecting from the world for a while.

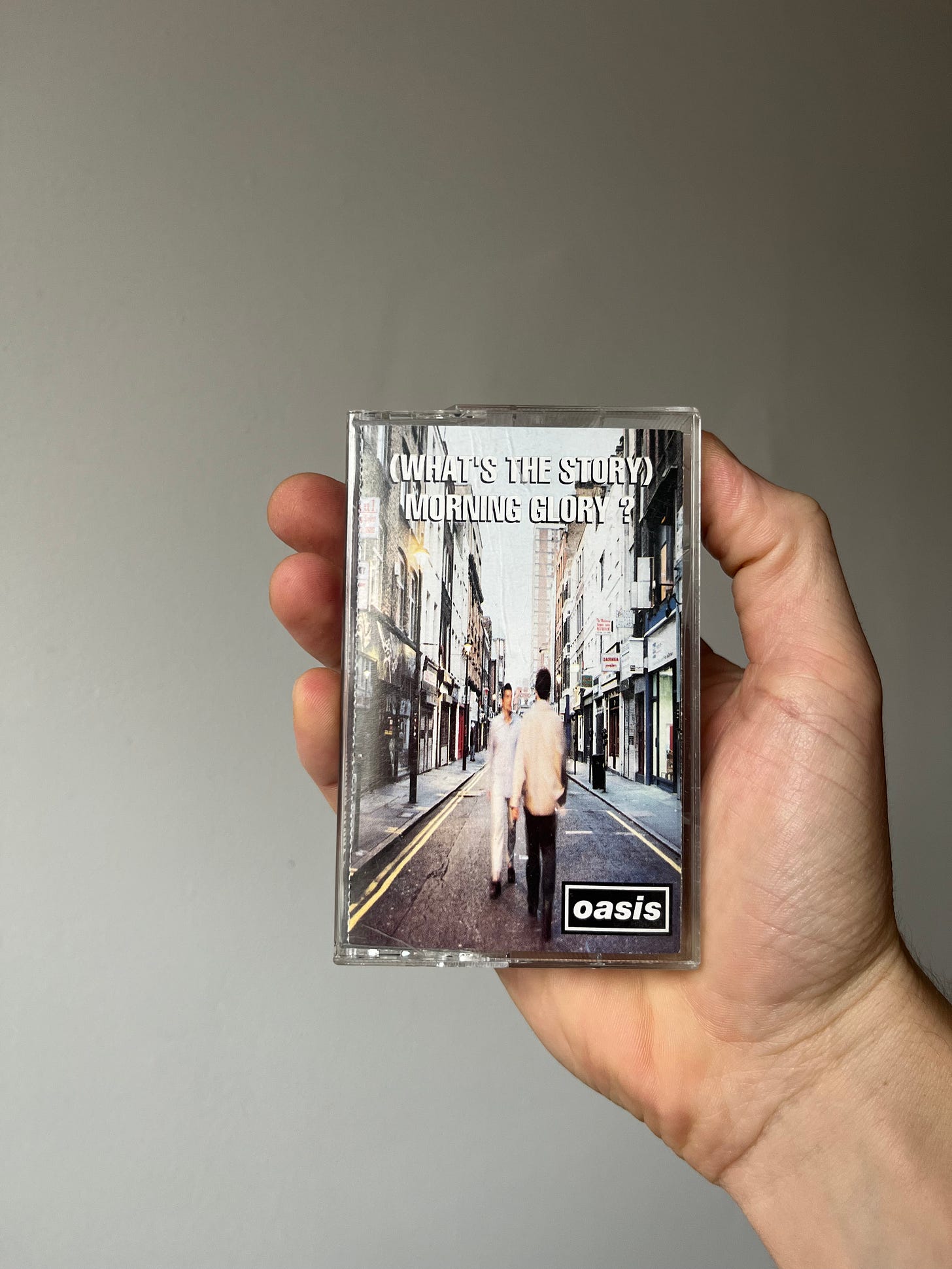

Because music has transitioned out of being a physical medium, it’s easy to lose a more tactile connection with it. I like tapes and records and CDs because they are music as a physical object, something I can hold onto, even if they’re not the primary format by which I listen to music. I’m not a purist by any measure, but as music loses its physical place in this world, it feels important to find a way for it to have physical space in my life.

There is an irreplaceable magic to spending sustained time with a set of songs— and that’s a practice that I can’t always unlock when I listen to music on Spotify. The convenience of streaming eats away at my ability to build a more intentional relationship with music: I hear music everywhere, but I’m not always listening.

The mechanics of listening change when you listen to a tape. You can’t easily skip a song because it doesn’t hit you with a hook right away. You have more patience because you have more time. Its physicality forces you to surrender, makes you more open to the authorial intent of the tape’s creator. This is one of the experiences we lose out on with Spotify— The sequence by which music comes into our life is either our own, distracted queuing, or the work of an algorithm. The recommendations are fine, but there are things to love about music that cannot be quantified, and we lose out on certain sonic experiences in this framework.

Gala gave me a copy of Oasis’ (What’s The Story) Morning Glory for Christmas. The ambient track that plays before Champagne Supernova is something I might skip if I were listening on my phone, but it adds so much dimension to the record to hear the song in its context. The sound of water on the shore by the studio shines through the cassette. You can hear the band there, clashing, playing, drinking, smoking, making that record. Sometimes I’ll leave my phone at home and walk around my neighborhood with that cassette in the walkman, mesmerized by the continuous forward roll of incredible songs on that album. The sequence is intentional but also organic. There is a clear beginning, middle, and end. You trust the people who made the album to guide you through the experience.

Music is so much more than content, but in our time we experience it as such. For a monthly fee, we have access to millions of recordings, pulled from thin air and severed from their context by the flat infinity of digital streaming platforms, recommended to us based on surveillance of our listening habits.

I want music to connect me to a real place, to real people, their taste, their history, their sensibility. Context is what makes our connection with music so vivid, and what keeps music alive. Lately I’ve been listening to a mixtape of songs that someone gave to me when I worked at a bar in the East Village. I put it on and it conjures the atmosphere of that time and place in my life. It’s a lot of proto pop-punk mixed in with 90s alt rock. The sequence draws connections between artists that a computer probably wouldn’t pick up on. In giving me the tape the person who made it, a musician himself with a lot of connections to underground music, brought me deeper into a world of music that I love, and that he has a deep knowledge of.

The sound is compressed, thin, and buzzy at times, but the tape’s distortions have a realistic effect on the listening experience— the high frequency hiss of the cassette breathes life into the drum cymbals and makes the music come alive, as if you’re in the room while the bands are playing. I can almost feel the sweat, taste the stale beer and smell the cigarette smoke when I put that tape on. Music can feel more real when it’s out of control, and this mix of songs benefits from the unpredictability of the format.

There is a lot at stake in our collective decision to disembody music, to make it a placeless thing. Because if music doesn’t have a place in our lives, it’s hard to pay close attention to. As Pelly writes in her book, these platforms exploit the placeless-ness they’ve created for profit. They make more money when we listen passively, and let their algorithms feed us music designed to blend into the background. The result is a watered down, homogenous music culture, full of sound bites that kind of sound like songs. It’s up to us, as people who love music, to find ways for it to be more than just background noise in our life.

I’m not writing this to convince you that you need to buy a walkman and listen to cassettes. It’s only one of a number of ways that songs enter my life. But I hope this piece inspires you to be more experimental in how you listen to music, because I think there is magic and subversion in challenging the ways we have all become passive listeners.

Music is the ocean I want to swim in too! And music in context is so important. We must keep cassettes and vinyl alive. Love this — very thoughtful.